Foot whipping

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

| Campaigns against corporal punishment |

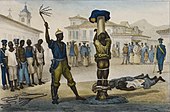

Foot whipping, falanga/falaka or bastinado is a method of inflicting pain and humiliation by administering a beating on the soles of a person's bare feet. Unlike most types of flogging, it is meant more to be painful than to cause actual injury to the victim. Blows are generally delivered with a light rod, knotted cord, or lash.[1]

Bastinado is also referred to as foot (bottom) caning or sole caning, depending on the instrument in use. The German term is Bastonade, deriving from the Italian noun bastonata (stroke with the use of a stick). In former times it was also referred to as Sohlenstreich (corr. striking the soles). The Chinese term is dǎ jiǎoxīn (打脚心 / 打腳心).

Overview

[edit]The first clearly identified written documentation of bastinado in Europe dates to 1537, and in China to 960.[2] References to bastinado have been hypothesised to also be found in the Bible (Prov. 22:15; Lev. 19:20; Deut. 22:18), suggesting use of the practice since antiquity.[3]

Bastinado was practiced in the Third Reich era. In several German and Austrian institutions it was still practised during the 1950s.[4][5][6][7]

Impact

[edit]Hyperpigmentation was found on torture victims' feet after months or years since being tortured. As a physical sign of torture, it can support requests for political asylum.[8]

Appearance

[edit]Regional

[edit]

Foot whipping was common practice as means of disciplinary punishment in different kinds of institutions throughout Central Europe until the 1950s, especially in German territories.[4][5]

In German prisons this method consistently served as the principal disciplinary punishment.[9] Throughout the Nazi era it was frequently used in German penal institutions and labour camps.

It was also inflicted on the population in occupied territories, notably Denmark and Norway.[6]

In Greece, during the Greek junta period, in a 1967 survey 83% of the inmates in Greek prisons reported about frequent infliction of bastinado. It was also used against rioting students. In Spanish prisons 39% of the inmates reported about this kind of treatment. The French Sûreté reportedly used it to extract confessions. The British used it in Palestine, and the French in Algeria. Within Colonial India it was used to punish tax offenders.[6]

Bastinado is still practised in penal institutions of several countries around the world.

In history

[edit]- The Bastinado was a common punishment during Mexico's Porfirian era, when the Rurales secret police would commonly use bull penises for the task.[10]

- In the United States, corporal punishment through foot whipping was reported from juvenile penal institutions until 1969, as for example in Massachusetts.[6]

- Foot whipping was practised in juvenile institutions and protectories in Austria until the 1960s.[11]

- In Nazi Germany caning the soles of a prisoner's bare feet was employed as a form of chastisement in concentration camps, prison camps and penitentiaries.[12][13][14]

- Indian Imperial Police officer Charles Tegart is said to have instituted foot whipping, a practice derived from Ottoman times, in an interrogation centre established at Jerusalem in 1938 as part of the effort to suppress the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine.

- Foot whipping was used by Fascist Blackshirts against Freemasons critical of Benito Mussolini as early as 1923 (Dalzell, 1961).

- It was used as a method of torture during the Greek Civil War of 1946 to 1949 and the regime of the Colonels from 1967 to 1974.[15]

- It was reported that Russian prisoners of war were "bastinadoed' at Afion camp by their Ottoman captors during World War I. However, British prisoners escaped this treatment.[16]

- Foot whipping was, among other methods, used as a method of obtaining confession from alleged political criminals during the communist regime of Czechoslovakia[17]

- Bahá'u'lláh (founder of the Baháʼí Faith) underwent foot whipping in August 1852. (Esslemont, 1937).

- Foot whipping was used at the S-21 prison in Phnom Penh during the rule of the Khmer Rouge and is mentioned in the ten regulations to prisoners now on display in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

- This punishment has, at various times, been used in China. "No crimes pass unpunished in China. The bastinado is the common punishment for slight faults, and the number of blows is proportionable to the nature of the fault... When the number of blows does not exceed twenty, it is accounted a fatherly correction. The emperor himself sometimes commands it to be inflicted on great persons, and afterwards sees them and treats them as usual."[18]

Modern era

[edit]

- Foot whipping was a commonly reported torture method used by the security officers of Bahrain on its citizens between 1974 and 2001.[19] See Torture in Bahrain.

- Falanga is allegedly used by the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) against persons suspected of involvement with the opposition Movement for Democratic Change parties (MDC-T and MDC-M).[20]

- The Prime Minister of Eswatini, Barnabas Sibusiso Dlamini, threatened to use this form of torture (sipakatane) to punish South African activists who had taken part in a mass protest for democracy in that country.[21]

- Reportedly used during the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein in Iraq (1979–2003).

- Reportedly used in Tunisia by security forces.[22]

- Recent research in imaging of torture victims confirms it is still used in several other countries.[23]

- Foot whipping amongst other methods is still practised today in the torture of prisoners in Russia.[24]

- Foot whipping is a common torture method in Saudi Arabia.[25]

In literature

[edit]- In act V, scene I of the Shakespearean comedy As You Like It, Touchstone threatens William with the line: "I will deal in poison with thee, or in bastinado, or in steel..."

- In act I, scene X of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera, Die Entführung aus dem Serail ("The Abduction from the Seraglio"), Osmin threatens Belmonte and Pedrillo with bastinado: "Sonst soll die Bastonade Euch gleich zu Diensten steh'n." (lit. "Or the bastonade will serve you soon.").

- In act I, scene XIX of Mozart's opera The Magic Flute, Sarastro orders Monostatos to be punished with 77 blows on the soles of his feet: "He! gebt dem Ehrenmann sogleich/nur sieben und siebenzig Sohlenstreich'." (lit. "Give the gentleman immediately just seventy-seven strokes on the soles.")

- In Chapter 8, Climatic Conditions, of Robert Irwin's novel The Arabian Nightmare, Sultan's doppelgänger is discovered and is questioned. "He was bastinadoed lightly to make him talk (for a heavy bastinado killed), but the man sobered up quickly and said nothing."

- In Chapter 58 of Innocents Abroad by Mark Twain, a member of Twain's party goes to collect a specimen from the face of the Sphinx and Twain sends a sheik to warn him of the consequences: "...by the laws of Egypt the crime he was attempting to commit was punishable with imprisonment or the bastinado."

- In Henri Charrière's Papillon, the author recalls having this done to him at Devil's Island, whereupon he had to be carried about in a wheelbarrow, with the soles of his feet resting against garden fork handles.

- In Tony Anthony's autobiography: Taming the Tiger, he was tortured and interrogated by Cyprian policemen using primarily this method, before being imprisoned in Nicosia central prison.

- When "Gonzo" journalist Hunter S. Thompson ran an unsuccessful campaign for Sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado, in 1970, he said his plan for dealing with the illicit drug trade was that "My first act as Sheriff will be to install, on the courthouse lawn, a bastinado platform and a set of stocks in order to punish dishonest dope dealers in a proper public fashion."[26][27]

- In Mario Puzo's novel of The Godfather, three corrupt home-repair workers are "thoroughly bastinadoed" by Sonny Corleone.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Flogging | punishment".

- ^ Rejali 2009, p. 274.

- ^ "Bastinado". www.biblegateway.com. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Wimmersdorf: 270 Schläge auf die Fußsohlen" (in German). kurier.at. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b "krone.at" vom 29. März 2012 Berichte über Folter im Kinderheim auf der Hohen Warte; 3 March 2014

- ^ a b c d Rejali 2009, p. 275.

- ^ Ruxandra Cesereanu: An Overview of Political Torture in the Twentieth Century. p. 124f.

- ^ Longstreth, George F; Grypma, Lydia; Willis, Brittney A; Anderson, Kathi C. "Foot Torture (Falanga): Ten Victims with Chronic Plantar Hyperpigmentation" (PDF). The American Journal of Medicine.

- ^ Hawkins, Francis Bisset (1839). Germany: The Spirit of Her History, Literature, Social Condition and National Economy : Illustrated by Reference to Her Physical, Moral, and Political Statistics, and by Comparison with Other Countries. Charles Jugel at the German and foreign library. p. 235.

- ^ McLynn, Frank (2001). Villa and Zapata: A Biography of the Mexican Revolution. Pimlico. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7126-6677-0.

- ^ „krone.at“ 29 March 2012 Berichte über Folter in Kinderheimen auf der Hohen Warte; 22 February 2014

- ^ Vgl. Ruxandra Cesereanu: An Overview of Political Torture in the Twentieth Century. S. 124f.

- ^ "Weibliche Angelegenheiten": Handlungsräume von KZ-Aufseherinnen in Ravensbrück und Neubrandenburg ("Female Matters": Responsibilities of overseers in the concentration camps of Ravensbrück and Neubrandenburg): [1] 1.6.2023

- ^ "Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung": Helga Schwarz u. Gerda Szepansky: ... und dennoch blühten Blumen (S. 26) ("Brandenburg Central for political education": ... and yet the flowers bloomed p. 26)[2] 1.6.2023

- ^ Pericles Korovessis, The Method: A Personal Account of the Tortures in Greece, trans. Les Nightingale and Catherine Patrarkis (London: Allison & Busby, 1970); extract in William F. Schulz, The Phenomenon of Torture: Readings and Commentary, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007, pp. 71-9.

- ^ Christopher Pugsley, Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story, Appendix 1, p. 357.

- ^ Kroupa, Mikuláš (10 March 2012). "Příběhy 20. století: Za vraždu estébáka se komunisté mstili torturou" [Tales of the 20th century: For the murder of a state security officer, the communists took revenge with torture]. iDnes (in Czech). Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks".

- ^ "E/CN.4/1997/7 Fifty-third session, Item 8(a) of the provisional agenda UN Doc., 10 January 1997". Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ "An Analysis of the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum Legal Cases, 1998-2006" Archived 21 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine (PDF).

- ^ Sibongile Sukati (9 September 2010). "Sipakatane for rowdy foreigners". Times of Swaziland. Mbabane.

- ^ "Justice en Tunisie : un printemps inachevé". ACAT. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Miller, Christine; Popelka, Jessica; Griffin, Nicole (8 June 2014). "Confirming Torture: The Use of Imaging in Victims of Falanga". www.forensicmag.com. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ "Leaked Video Blows Lid off Torture in Russian Prisons". Human Rights Watch. Russia. 30 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: Reports of torture and sexual harassment of detained activists | Amnesty International". Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ Barker, Christian (October 2016). "The Clothes of Hunter S. Thompson". The Rake.

- ^ Willis, David (3 September 2020). "When Hunter S. Thompson Ran for Sheriff". Literary Hub.

Sources

[edit]- Rejali, Darius (2009). Torture and Democracy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691143330.