Kirk Douglas

Kirk Douglas | |

|---|---|

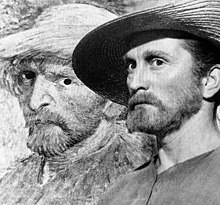

Douglas in 1963 | |

| Born | Issur Danielovitch December 9, 1916 Amsterdam, New York, U.S. |

| Died | February 5, 2020 (aged 103) |

| Resting place | Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, Westwood, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Alma mater | St. Lawrence University |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1944–2008 |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Military career | |

| Service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1941–1944 |

| Website | www |

| Signature | |

| |

Kirk Douglas (born Issur Danielovitch; December 9, 1916 – February 5, 2020) was an American actor and filmmaker. After an impoverished childhood, he made his film debut in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946) with Barbara Stanwyck. Douglas soon developed into a leading box-office star throughout the 1950s, known for serious dramas, including westerns and war films. During his career, he appeared in more than 90 films and was known for his explosive acting style. He was named by the American Film Institute the 17th-greatest male star of Classic Hollywood cinema.

Douglas played an unscrupulous boxing hero in Champion (1949), which brought him his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor. His other early films include Out of the Past (1947); Young Man with a Horn (1950), playing opposite Lauren Bacall and Doris Day; Ace in the Hole (1951); and Detective Story (1951), for which he received a Golden Globe nomination. He received his second Oscar nomination for his dramatic role in The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), opposite Lana Turner, and earned his third for portraying Vincent van Gogh in Lust for Life (1956), a role for which he won the Golden Globe for the Best Actor in a Drama. He also starred with James Mason in the adventure 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), a large box-office hit.

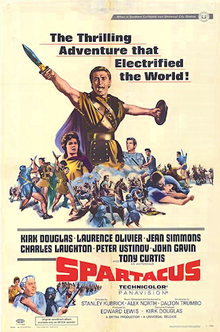

In September 1949, he established Bryna Productions, which began producing films as varied as Paths of Glory (1957) and Spartacus (1960). In those two films, he collaborated with the then relatively unknown director Stanley Kubrick, taking lead roles in both films. Douglas helped to break the Hollywood blacklist by having Dalton Trumbo write Spartacus with an official on-screen credit.[1] He produced and starred in Lonely Are the Brave (1962) and Seven Days in May (1964), the latter opposite Burt Lancaster, with whom he made seven films. In 1963, he starred in the Broadway play One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, a story that he purchased and later gave to his son Michael Douglas, who turned it into an Oscar-winning film. Douglas continued acting into the 1980s, appearing in such films as Saturn 3 (1980), The Man from Snowy River (1980), Tough Guys (1986), a reunion with Lancaster, and in the television version of Inherit the Wind (1988) plus in an episode of Touched by an Angel in 2000, for which he received his third nomination for an Emmy Award.

As an actor and philanthropist, Douglas received an Academy Honorary Award for Lifetime Achievement and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. As an author, he wrote ten novels and memoirs. After barely surviving a helicopter crash in 1991 and then suffering a stroke in 1996, he focused on renewing his spiritual and religious life. He lived with his second wife, producer Anne Buydens, until his death in 2020. A centenarian, Douglas was one of the last surviving stars of the film industry's Golden Age.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Douglas was born Issur Danielovitch[a] in Amsterdam, New York, on December 9, 1916, the fourth of seven children and the only son of Bryna "Bertha" (née Sanglel) and Herschel "Harry" Danielovitch.[3] His parents were Jewish immigrants from Chavusy, Mogilev Governorate, in the Russian Empire (present-day Belarus),[4][5][6][7][8][9] and the family spoke Yiddish at home.[10][11][12][13] His sisters were: Pesha "Bessie", Kaleh "Katherine", Tamara "Mary", Siffra "Frieda",[14] Haska "Ida", and Rachel "Ruth".[15] Douglas embraced his Jewish heritage after a near-fatal helicopter crash at the age of 74.[16]

His father's brother, who had immigrated earlier, used the surname Demsky, which Douglas's family adopted in the United States.[17]: 2 Douglas grew up as Izzy Demsky and legally changed his name to Kirk Douglas before entering the United States Navy during World War II.[18][b]

In his 1988 autobiography, The Ragman's Son, Douglas notes the hardships that he, along with his parents and six sisters, endured during their early years in Amsterdam:

My father, who had been a horse trader in Russia, got himself a horse and a small wagon, and became a ragman, buying old rags, pieces of metal, and junk for pennies, nickels, and dimes ... Even on Eagle Street, in the poorest section of town, where all the families were struggling, the ragman was on the lowest rung on the ladder. And I was the ragman's son.[19]

Douglas had an unhappy childhood, living with an alcoholic, physically abusive father.[20] While his father drank up what little money they had, Douglas and his mother and sisters endured "crippling poverty".[21]

Douglas first wanted to be an actor after he recited "The Red Robin of Spring", a poem by the English poet John Clare, while in kindergarten and received applause.[22] Growing up, he sold snacks to mill workers to earn enough to buy milk and bread to help his family. He later delivered newspapers, and he had more than forty jobs during his youth before becoming an actor.[23] He found living in a family with six sisters to be stifling: "I was dying to get out. In a sense, it lit a fire under me." After appearing in plays at Amsterdam High School, from which he graduated in 1934,[24] he knew he wanted to become a professional actor.[25] Unable to afford the tuition, Douglas talked his way into the dean's office at St. Lawrence University and showed him a list of his high school honors. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1939. He received a loan which he paid back by working part-time as a gardener and a janitor. He was a standout on the school's wrestling team and wrestled one summer in a carnival to make money.[26] He later became good friends with world-champion wrestler Lou Thesz.

Douglas's acting talents were noticed at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City, which gave him a special scholarship. One of his classmates was Betty Joan Perske (later known as Lauren Bacall), who would play an important role in launching his film career.[27] Bacall wrote that she "had a wild crush on Kirk",[28] and they dated casually. Another classmate, and a friend of Bacall's, was aspiring actress Diana Dill, who would later become Douglas's first wife.[citation needed]

During their time together, Bacall learned Douglas had no money and that he once spent the night in jail since he had no place to sleep. She once gave him her uncle's old coat to keep warm: "I thought he must be frozen in the winter ... He was thrilled and grateful." Sometimes, just to see him, she would drag a friend or her mother to the restaurant where he worked as a busboy and waiter. He told her his dream was to someday bring his family to New York to see him on stage. During that period she fantasized about someday sharing her personal and stage lives with Douglas, but would later be disappointed: "Kirk did not really pursue me. He was friendly and sweet—enjoyed my company—but I was clearly too young for him," the eight-years-younger Bacall later wrote.[28]

Career

[edit]Rise to stardom

[edit]Douglas joined the United States Navy in 1941, shortly after the United States entered World War II, where he served as a communications officer in anti-submarine warfare aboard USS PC-1139.[29] He was medically discharged in 1944 for injuries sustained from the premature explosion of a depth charge.[30] He rose to the rank of Lieutenant (junior grade).[29]

After the war, Douglas returned to New York City and found work in radio, theater, and commercials. In his radio work, he acted in network soap operas and saw those experiences as being especially valuable, as skill in using one's voice is important for aspiring actors; he regretted that later the same avenues became no longer available. His stage break occurred when he took over the role played by Richard Widmark in Kiss and Tell (1943), which then led to other offers.[27]

Douglas had planned to remain a stage actor until his friend Lauren Bacall helped him get his first film role by recommending him to producer Hal B. Wallis, who was looking for a new male talent.[31] Wallis's film The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946) with Barbara Stanwyck became Douglas' debut screen appearance. He played a young, insecure man stung by jealousy, whose life was dominated by his ruthless wife, and who hid his feelings with alcohol. It would be the last time that Douglas portrayed a weakling in a film role.[32][33] Reviewers of the film noted that Douglas already projected qualities of a "natural film actor", with the similarity of this role with later ones explained by biographer Tony Thomas:

His style and his personality came across on the screen, something that does not always happen, even with the finest actors. Douglas had, and has, a distinctly individual manner. He radiates a certain inexplicable quality, and it is this, as much as talent, that accounts for his success in films.[34]

In 1947, Douglas appeared in Out of the Past (UK: Build My Gallows High), playing a large supporting role in this classic noir thriller starring Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer. Douglas made his Broadway debut in 1949 in Three Sisters, produced by Katharine Cornell.[35] The month after Out of the Past was released, I Walk Alone, the first film teaming Douglas with Burt Lancaster, presented Douglas playing a supporting part quite similar to his role in Out of the Past in another classic fast-paced noir thriller.

Douglas' image as a tough guy was established in his eighth film, Champion (1949), after producer Stanley Kramer chose him to play a selfish boxer. In accepting the role, he took a gamble, however, since he had to turn down an offer to star in a big-budget MGM film, The Great Sinner, which would have earned him three times the income.[36][37] Melvyn Douglas played the third-billed (above the title) part Kirk Douglas passed on. The Great Sinner flopped.

Film historian Ray Didinger says Douglas "saw Champion as a greater risk, but also a greater opportunity ... Douglas took the part and absolutely nailed it." Frederick Romano, another sports film historian, described Douglas's acting as "alarmingly authentic":

Douglas shows great concentration in the ring. His intense focus on his opponent draws the viewer into the ring. Perhaps his best characteristic is his patented snarl and grimace ... he leaves no doubt that he is a man on a mission.[38]

Douglas received his first Academy Award nomination, and the film earned six nominations in all. Variety called it "a stark, realistic study of the boxing rackets."[37]

After Champion he decided that, to succeed as a star, he needed to ramp up his intensity, overcome his natural shyness, and choose stronger roles. He later stated, "I don't think I'd be much of an actor without vanity. And I'm not interested in being a 'modest actor'".[39] Early in his Hollywood career, Douglas demonstrated his independent streak and broke his studio contracts to gain total control over his projects, forming his own movie company, Bryna Productions (named after his mother) in September 1949.[25][40]

Peak years of success

[edit]

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Douglas was a major box-office star, playing opposite some of the leading actresses of that era. He portrayed a frontier peace officer in his first western, Along the Great Divide (1951). He quickly became very comfortable with riding horses and playing gunslingers, and he appeared in many Westerns. He considered Lonely Are the Brave (1962), in which he plays a cowboy trying to live by his own code, his personal favorite.[41] The film, written by Dalton Trumbo, was respected by critics but did not do well at the box office due to poor marketing and distribution.[39][42]

In 1950, Douglas played Rick Martin in Young Man with a Horn, based on a novel of the same name by Dorothy Baker based on the life of jazz cornetist Bix Beiderbecke. Composer and pianist Hoagy Carmichael, a friend of the real Beiderbecke, played the sidekick, adding realism to the film and giving Douglas insight into the role.[43] Doris Day starred as Jo, a young woman who was infatuated with the struggling jazz musician. This was strikingly opposite of the real-life account in Doris Day's autobiography, which described Douglas as "civil but self-centered" and the film as "utterly joyless".[44] During filming, bit actress Jean Spangler disappeared, and her case remains unsolved. On October 9, 1949, Spangler's purse was found near the Fern Dell entrance to Griffith Park in Los Angeles. There was an unfinished note in the purse addressed to a "Kirk," which read: "Can't wait any longer, Going to see Dr. Scott. It will work best this way while mother is away". Douglas, married at the time, called the police and told them he was not the Kirk mentioned in the note. When interviewed via telephone by the head of the investigating team, Douglas stated that he had "talked and kidded with her a bit" on set,[45][46] but that he had never been out with her.[47] Spangler's girlfriends told police that she was three months pregnant when she disappeared,[48] and scholars such as Jon Lewis of Oregon State University have speculated that she may have been considering an illegal abortion.[49]

In 1951, Douglas starred as a newspaper reporter anxiously looking for a big story in Ace in the Hole, director Billy Wilder's first effort as both writer and producer. The subject and story was controversial at the time, and U.S. audiences stayed away. Some reviews saw it as "ruthless and cynical ... a distorted study of corruption, mob psychology and the free press."[50] Possibly it "hit too close to home", said Douglas.[51] It won a Best Foreign Film award at the Venice Film Festival. The film's stature has increased in recent years, with some surveys placing it in their Top 500 Films list.[52] Woody Allen considers it one of his favorite films.[53] As the film's star and protagonist, Douglas is credited for the intensity of his acting. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote, "his focus and energy ... is almost scary. There is nothing dated about Douglas' performance. It's as right-now as a sharpened knife."[54] Biographer Gene Philips noted that Wilder's story was "galvanized" by Douglas's "astounding performance" and no doubt was a factor when George Stevens, who presented Douglas with the AFI Life Achievement Award in 1991, said of him: "No other leading actor was ever more ready to tap the dark, desperate side of the soul and thus to reveal the complexity of human nature."[55]

Also in 1951, Douglas starred in Detective Story, nominated for four Academy Awards, including one for Lee Grant in her debut film. Grant said Douglas was "dazzling, both personally and in the part. ... He was a big, big star. Gorgeous. Intense. Amazing."[56] To prepare for the role, Douglas spent days with the New York Police Department and sat in on interrogations.[57] Reviewers recognized Douglas's acting qualities, with Bosley Crowther describing Douglas as "forceful and aggressive as the detective".[58]

In The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), another of his three Oscar-nominated roles, Douglas played a hard-nosed film producer who manipulates and uses his actors, writers, and directors. In 1954 Douglas starred as the titular character in Ulysses, a film based on Homer's epic poem Odyssey, with Silvana Mangano as Penelope and Circe, and Anthony Quinn as Antinous.[59]

In 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Douglas showed that in addition to serious, driven characters, he was adept at roles requiring a lighter, comic touch. In this adaptation of the Jules Verne novel, he played a happy-go-lucky sailor who was the opposite in every way to the brooding Captain Nemo (James Mason). The film was one of Walt Disney's most successful live-action movies and a major box-office hit.[60] Douglas managed a similar comic turn in the western Man Without a Star (1955) and in For Love or Money (1963). He showed further diversity in one of his earliest television appearances. He was a musical guest (as himself) on The Jack Benny Program (1954).[61]

In 1955, Douglas was finally able to get his film production company, Bryna Productions, off the ground.[25] To do so, he had to break contracts with Hal B. Wallis and Warner Bros., but he began to produce and star in his own films, starting with The Indian Fighter in 1955.[62] Through Bryna, he produced and starred in the films Paths of Glory (1957), The Vikings (1958), Spartacus (1960), Lonely are the Brave (1962), and Seven Days in May (1964).[63] In 1958, Douglas formed the music publishing company Peter Vincent Music Corporation, a Bryna Productions subsidiary.[64] Peter Vincent Music was responsible for publishing the soundtracks of The Vikings and Spartacus.[64][65]

While Paths of Glory did not do well at the box office, it has since become one of the great anti-war films, and it is one of director Stanley Kubrick's early films. Douglas, a fluent French speaker,[66] portrayed a sympathetic French officer during World War I who tries to save three soldiers from facing a firing squad.[67] Biographer Vincent LoBrutto describes Douglas's "seething but controlled portrayal exploding with the passion of his convictions at the injustice leveled at his men."[68] The film was banned in France until 1976. Before production of the film began, however, Douglas and Kubrick had to work out some large problems, one of which was Kubrick's rewriting the screenplay without informing Douglas first. It led to their first major argument: "I called Stanley to my room ... I hit the ceiling. I called him every four-letter word I could think of ... 'I got the money, based on that [original] script. Not this shit!' I threw the script across the room. 'We're going back to the original script, or we're not making the picture.' Stanley never blinked an eye. We shot the original script. I think the movie is a classic, one of the most important pictures—possibly the most important picture—Stanley Kubrick has ever made."[68]

Douglas played military men in numerous films, with varying nuance, including Top Secret Affair (1957), Town Without Pity (1961), The Hook (1963), Seven Days in May (1964), Heroes of Telemark (1965), In Harm's Way (1965), Cast a Giant Shadow (1966), Is Paris Burning (1966), The Final Countdown (1980), and Saturn 3 (1980). His acting style and delivery made him a favorite with television impersonators such as Frank Gorshin, Rich Little, and David Frye.[69][70][71]

His role as Vincent van Gogh in Lust for Life (1956), directed by Vincente Minnelli and based on Irving Stone's bestseller, was filmed mostly on location in France. Douglas was noted not only for the veracity of van Gogh's appearance but for how he conveyed the painter's internal turmoil. Some reviewers consider it the most famous example of the "tortured artist" who seeks solace from life's pain through his work.[72] Others see it as a portrayal not only of the "painter-as-hero", but a unique presentation of the "action painter", with Douglas expressing the physicality and emotion of painting, as he uses the canvas to capture a moment in time.[73][74]

Douglas was nominated for an Academy Award for the role, with his co-star Anthony Quinn winning the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor as Paul Gauguin, van Gogh's friend. Douglas won a Golden Globe award, although Minnelli said Douglas should have won an Oscar: "He achieved a moving and memorable portrait of the artist—a man of massive creative power, triggered by severe emotional stress, the fear and horror of madness."[60] Douglas himself called his acting role as Van Gogh a painful experience: "Not only did I look like Van Gogh, I was the same age he was when he committed suicide."[75] His wife said he often remained in character in his personal life: "When he was doing Lust for Life, he came home in that red beard of Van Gogh's, wearing those big boots, stomping around the house—it was frightening."[76]

In general, however, Douglas's acting style fit well with Minnelli's preference for "melodrama and neurotic-artist roles", writes film historian James Naremore. He adds that Minnelli had his "richest, most impressive collaborations" with Douglas, and for Minnelli, no other actor portrayed his level of "cool": "A robust, athletic, sometimes explosive player, Douglas loved stagy rhetoric, and he did everything passionately."[77] Douglas had also starred in Minnelli's film The Bad and the Beautiful four years earlier, for which he received a Best Actor Oscar nomination.[78]

Financial troubles

[edit]For approximately 15 years and 27 films, Douglas's agent had been Sam Norton, who was compensated with 10% of Douglas's gross earnings. In addition, Norton was partners with Jerome “Jerry” B. Rosenthal in the law firm of Rosenthal & Norton which received an additional 10%.[79] On the day of his wedding in 1958 his bride Anne had been quietly pulled aside by Norton and been presented by Norton (without Kirk Douglas's knowledge) with a pre-nuptial agreement. She signed the document, but Douglas, because he held Norton as both his best friend and a father figure, was unwilling to get involved in his wife's subsequent attempts to obtain a copy.[79] Anne Douglas went behind her husband's back, engaging lawyer Greg Bautzer and suing to obtain a copy from Norton successfully. Her distrust of Norton grew, especially as he had been granted power of attorney, and she found that the pre-nuptial agreement meant that she and their children had no claim on Douglas's estate until they had been married for five years. She could also find no documentation to prove Norton's assertion that Douglas was a millionaire. Her suspicions were further aroused when the Broadway play A Very Special Baby for which Norton had convinced Douglas to guarantee financing, closed after only a week. She shared her concerns first with Greg Bautzer and then Edward Lewis who advised her to hire Price Waterhouse to investigate her husband's finances.[79]

Douglas returned from filming The Devils Disciple in England in late 1958, and was presented with the results of Price Waterhouse's audit which detailed that the 18 months he had recently spent overseas on the advice of Norton did not qualify for a tax-free income break, that the investments he had been advised to make in fact had been channeled through dummy companies owned by his agent. As a result, Douglas had no money and owed the IRS $750,000. Douglas engaged a new lawyer and was able to get Rosenthal & Norton to give up their rights to any interest in his latest film The Vikings and any of his future income. Norton was dismissed as his agent, but as he had put nearly all of his assets in his wife's name, Douglas was only able to recover $200,000 from him.[79]

The profits from The Vikings allowed Douglas to pay off his IRS debt, with his financial future now dependent on the success of Spartacus.[79]

Spartacus and mid-career

[edit]

In 1960, Douglas played the title role in what many consider his career-defining appearance[80] as the Thracian gladiator slave rebel Spartacus with an all-star cast in Spartacus (1960). He was the executive producer as well, which increased the $12 million production cost and made Spartacus one of the most expensive films up to that time.[81] Douglas initially selected Anthony Mann to direct, but replaced him early on with Stanley Kubrick, with whom he had previously collaborated in Paths of Glory.[82]

When the film was released, Douglas gave full credit to its screenwriter, Dalton Trumbo, who was on the Hollywood blacklist, and thereby effectively ended it.[17]: 81 During a 2012 interview Douglas said, "I've made over 85 pictures, but the thing I'm most proud of is breaking the blacklist."[5] The film's producer, Edward Lewis, and the family of Dalton Trumbo publicly disputed Douglas's claim.[83] In the film Trumbo (2015), Douglas is portrayed by Dean O'Gorman.[84]

Douglas bought the rights to stage a play of the novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest from its author, Ken Kesey. He mounted a play from the material in 1963 in which he starred and that ran on Broadway for five months. Reviews were mixed. Douglas retained the movie rights due to an innovative loophole of basing the rights on the play rather than the novel, despite Kesey's objections, but after a decade of being unable to find a producer he gave the rights to his son, Michael. In 1975, the film version was produced by Michael Douglas and Saul Zaentz, and starred Jack Nicholson, as Douglas was then considered too old to play the character as written.[2] The film won all five major Academy Awards, only the second film to do so (after It Happened One Night in 1934).[85]

Douglas made seven films over four decades with actor Burt Lancaster: I Walk Alone (1947), Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), The Devil's Disciple (1959), The List of Adrian Messenger (1963), Seven Days in May (1964), Victory at Entebbe (1976), and Tough Guys (1986), which fixed the notion of the pair as something of a team in the public imagination. Douglas was always billed under Lancaster in these movies, but, with the exception of I Walk Alone and, even more so, The List of Adrian Messenger (where Lancaster's part is just a cameo appearance, while Douglas plays the film's villain), their roles were usually of a similar size. Both actors arrived in Hollywood at about the same time and first appeared together in the fourth film for each, albeit with Douglas in a supporting role. They both became actor-producers who sought out independent Hollywood careers.[76]

John Frankenheimer, who directed the political thriller Seven Days in May in 1964, had not worked well with Lancaster in the past and originally did not want him in this film. However, Douglas thought Lancaster would fit the part and "begged me to reconsider," said Frankenheimer, and he then gave Lancaster the most colorful role. "It turns out that Burt Lancaster and I got along magnificently well on the picture," he later said.[86]

In 1967 Douglas starred with John Wayne in the western film directed by Burt Kennedy titled The War Wagon.[87]

In The Arrangement (1969), a drama directed by Elia Kazan and based upon his novel of the same title, Douglas starred as a tormented advertising executive, with Faye Dunaway as costar. The film did poorly at the box office, receiving mostly negative reviews. Dunaway believed many of the reviews were unfair, writing in her biography, "I can't understand it when people knock Kirk's performance, because I think he's terrific in the picture," adding that "he's as bright a person as I've met in the acting profession."[88] She says that his "pragmatic approach to acting" would later be a "philosophy that ended up rubbing off on me."[89]

Later work

[edit]

In the 1970s, he starred in films such as There Was a Crooked Man... (1970),[90] A Gunfight (1971),[91] The Light at the Edge of the World (1971).[92] and The Fury (1978).[93] He made his directorial debut in Scalawag. (1973),[94] and subsequently also directed Posse (1975), in which he starred alongside Bruce Dern.[95]

In 1980, he starred in The Final Countdown,[96] playing the commanding officer of the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, which travels through time to the day before the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. It was produced by his son Peter Douglas. He also played in a dual role in The Man from Snowy River (1982), an Australian film which received critical acclaim and numerous awards.

In 1986, he reunited with his longtime co-star, Burt Lancaster, in a crime comedy, Tough Guys, with a cast including Charles Durning and Eli Wallach. It marked the final collaboration between Douglas and Lancaster, completing a partnership of more than 40 years.[97] That same year, he co-hosted (with Angela Lansbury) the New York Philharmonic's tribute to the 100th anniversary of the Statue of Liberty. The symphony was conducted by Zubin Mehta.[98]

In 1988, Douglas starred in a television adaptation of Inherit the Wind, opposite Jason Robards and Jean Simmons. The film won two Emmy Awards. In the 1990s, Douglas continued starring in various features. Among them was The Secret in 1992, a television movie about a grandfather and his grandson who both struggle with dyslexia. That same year, he played the uncle of Michael J. Fox in a comedy, Greedy. He appeared as the Devil in the video for the Don Henley song "The Garden of Allah". In 1996, after suffering a severe stroke at age 79 which impaired his ability to speak, Douglas still wanted to make movies. He underwent years of voice therapy and made Diamonds in 1999, in which he played an old professional boxer who was recovering from a stroke. It co-starred his longtime friend from his early acting years, Lauren Bacall.[99]

In 2003, Michael and Joel Douglas produced It Runs in the Family, which along with Kirk starred various family members, including Michael, Michael's son Cameron, and his wife from 50 years earlier, Diana Dill, playing his wife. His final feature-film appearance was in the 2004 Michael Goorjian film Illusion, in which he depicts a dying film director forced to watch episodes from the life of a son he had refused to acknowledge.[100][101][102] His last screen role was the TV movie Empire State Building Murders, which was released in 2008.[100] In March 2009, at the age of 92, Douglas performed an autobiographical one-man show, Before I Forget, at the Center Theatre Group's Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City, California. The four performances were filmed and turned into a documentary that was first screened in January 2010.[103]

On December 9, 2016, he celebrated his 100th birthday at the Beverly Hills Hotel, joined by several of his friends, including Don Rickles, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Steven Spielberg, along with Douglas's wife Anne, his son Michael and his daughter-in-law Catherine Zeta-Jones. Douglas was described by his guests as still being in good shape, able to walk with confidence into the Sunset Room for the celebration.[104]

Douglas appeared at the 2018 Golden Globes with his daughter-in-law Catherine Zeta-Jones, a rare public appearance in the final decade of his life.[105] He received a standing ovation and helped Zeta-Jones present the award for "Best Screenplay – Motion Picture".[106]

Style and philosophy of acting

[edit]

Kirk is one of a kind. He has an overpowering physical presence, which is why on a large movie screen he looms over the audience like a tidal wave in full flood. Globally revered, he is now the last living screen legend of those who vaulted to stardom at the war's end, that special breed of movie idol instantly recognizable anywhere, whose luminous on-screen characters are forever memorable.

Douglas stated that the keys to acting success are determination and application: "You must know how to function and how to maintain yourself, and you must have a love of what you do. But an actor also needs great good luck. I have had that luck."[107] Douglas had great vitality and explained that "it takes a lot out of you to work in this business. Many people fall by the wayside because they don't have the energy to sustain their talent."[108]

That attitude toward acting became evident with Champion (1949). From that one role, writes biographer John Parker, he went from stardom and entered the "superleague", where his style was in "marked contrast to Hollywood's other leading men at the time".[31] His sudden rise to prominence is explained by comparing it to that of Jack Nicholson's:

He virtually ignored interventionist directors. He prepared himself privately for each role he played, so that when the cameras were ready to roll he was suitably, and some would say egotistically and even selfishly, inspired to steal every scene in a manner comparable in modern times to Jack Nicholson's modus operandi.[31]

As a producer, Douglas had a reputation of being a compulsively hard worker who expected others to exude the same level of energy. As such, he was typically demanding and direct in his dealing with people who worked on his projects, with his intensity spilling over into all elements of his film-making.[34] This was partly due to his high opinion of actors, movies, and moviemaking: "To me it is the most important art form—it is an art, and it includes all the elements of the modern age." He also stressed prioritizing the entertainment goal of films over any messages, "You can make a statement, you can say something, but it must be entertaining."[39]

As an actor, he dived into every role, dissecting not only his own lines but all the parts in the script to measure the rightness of the role, and he was willing to fight with a director if he felt justified.[108] Melville Shavelson, who produced and directed Cast a Giant Shadow (1966), said that it didn't take him long to discover what his main problem was going to be in directing Douglas:

Kirk Douglas was intelligent. When discussing a script with actors, I have always found it necessary to remember that they never read the other actors' lines, so their concept of the story is somewhat hazy. Kirk had not only read the lines of everyone in the picture, he had also read the stage directions ... Kirk, I was to discover, always read every word, discussed every word, always argued every scene, until he was convinced of its correctness. ... He listened, so it was necessary to fight every minute.[108]

For most of his career, Douglas enjoyed good health and what seemed like an inexhaustible supply of energy. He attributed much of that vitality to his childhood and pre-acting years: "The drive that got me out of my hometown and through college is part of the makeup that I utilize in my work. It's a constant fight, and it's tough."[108] His demands on others, however, were an expression of the demands he placed on himself, rooted in his youth. "It took me years to concentrate on being a human being—I was too busy scrounging for money and food, and struggling to better myself."[109]

Actress Lee Grant, who acted with him and later filmed a documentary about him and his family, notes that even after he achieved worldwide stardom, his father would not acknowledge his success. He said "nothing. Ever."[56] Douglas's wife, Anne, similarly attributes the energy he devotes to acting to his tough childhood:

He was reared by his mother and his sisters and as a schoolboy he had to work to help support the family. I think part of Kirk's life has been a monstrous effort to prove himself and gain recognition in the eyes of his father ... Not even four years of psychoanalysis could alter the drives that began as a desire to prove himself.[69]

Douglas has credited his mother, Bryna, for instilling in him the importance of "gambling on yourself", and he kept her advice in mind when making films.[34] Bryna Productions was named in her honor. Douglas realized that his intense style of acting was something of a shield: "Acting is the most direct way of escaping reality, and in my case it was a means of escaping a drab and dismal background."[110]

Personal life

[edit]Personality

[edit]In The Ragman's Son, Douglas described himself as a "son of a bitch," adding, "I'm probably the most disliked actor in Hollywood. And I feel pretty good about it. Because that's me... . I was born aggressive, and I guess I'll die aggressive."[7] Co-workers and associates alike noted similar traits, with Burt Lancaster once remarking, "Kirk would be the first to tell you that he is a very difficult man. And I would be the second."[111] Douglas's brash personality is attributed to his difficult upbringing living in poverty and his aggressive alcoholic father who was neglectful of Kirk as a young child.[7][112] According to Douglas, "there was an awful lot of rage churning around inside me, rage that I was afraid to reveal because there was so much more of it, and so much stronger, in my father."[112] Douglas' discipline, wit and sense of humor were also often recognized.[7]

Marriages and children

[edit]

Douglas and his first wife, Diana Dill, married on November 2, 1943. They had two sons, actor Michael Douglas and producer Joel Douglas, before divorcing in 1951.

According to his autobiography The Ragman's Son, he and Italian actress Pier Angeli were engaged in the early 1950s after meeting on the set of the film The Story of Three Loves (1953), but they never made it down the aisle.[113] Afterwards, in Paris, he met producer Anne Buydens (born Hannelore Marx; April 23, 1919, Hanover, Germany) while acting on location in Act of Love.[114] She originally fled from Germany to escape Nazism and survived by putting her multilingual skills to work at a film studio, creating translations for subtitles.[115] They married on May 29, 1954. In 2014, they celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary at the Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills.[116] They had two sons, Peter, a producer, and Eric, an actor who died on July 6, 2004, from an overdose of alcohol and drugs at the age of 46.[117] In 2017, the couple released a book, Kirk and Anne: Letters of Love, Laughter and a Lifetime in Hollywood, that revealed intimate letters they shared through the years.[118] Throughout their marriage, Douglas had affairs with other women, including several Hollywood starlets. He never hid his infidelities from his wife, who was accepting of them and explained, "as a European, I understood it was unrealistic to expect total fidelity in a marriage."[119]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mike Todd

[edit]Douglas was good friends with producer Mike Todd who lived across the street from him in Palm Springs.[120] On the morning of March 22, 1958, they were playing tennis when Todd asked him to come with him later that day on his private aircraft to New York, where he was due to receive an award.[120] He suggested that Douglas could make the presentation to him and afterwards on the way back they could stop and visit former president Harry Truman in Independence, Missouri.

Upon hearing of the plan, Douglas's wife Anne had an uneasy feeling and urged him to take a commercial flight instead. After a heated argument about the matter, Douglas in a temper said that if he could not fly with Todd then he would not go at all.[120]

The next morning while driving in the car to Los Angeles, Douglas and his family heard on the radio the news that Todd's aircraft had crashed a few hours after takeoff, killing all on board.[120]

Religion

[edit]On February 13, 1991, aged 74, Douglas was in a helicopter and was injured when the aircraft collided with a small plane above Santa Paula Airport. Two other people were also injured, including Noel Blanc, the son of voice actor Mel Blanc who was piloting the helicopter, and two people in the plane were killed.[121][122] This near-death experience sparked a search for meaning by Douglas, which led him, after much study, to embrace the Judaism in which he had been raised. He documented this spiritual journey in his book, Climbing the Mountain: My Search for Meaning (1997).[123]

He decided to visit Jerusalem again and wanted to see the Western Wall Tunnel during a trip where he would dedicate two playgrounds he donated to the state. His tour guide arranged to end the tour of the tunnel at the bedrock where, according to Jewish tradition, Abraham's binding of Isaac took place.[124]

In his earlier autobiography, The Ragman's Son, he recalled, "years back, I tried to forget that I was a Jew," but later in his career he began "coming to grips with what it means to be a Jew," which became a theme in his life.[125] In an interview in 2000, he explained this transition:[126]

Judaism and I parted ways a long time ago, when I was a poor kid growing up in Amsterdam, N.Y. Back then, I was pretty good in cheder, so the Jews of our community thought they would do a wonderful thing and collect enough money to send me to a yeshiva to become a rabbi. Holy Moses! That scared the hell out of me. I didn't want to be a rabbi. I wanted to be an actor. Believe me, the members of the Sons of Israel were persistent. I had nightmares – wearing long payos and a black hat. I had to work very hard to get out of it. But it took me a long time to learn that you don't have to be a rabbi to be a Jew.

Douglas noted that an underlying theme of some of his films, including The Juggler (1953), Cast a Giant Shadow (1966), and Remembrance of Love (1982), was about "a Jew who doesn't think of himself as one, and eventually finds his Jewishness."[125] The Juggler was the first Hollywood feature to be filmed in the newly established state of Israel. Douglas recalled that, while there, he saw "extreme poverty and food being rationed." But he found it "wonderful, finally, to be in the majority." The film's producer, Stanley Kramer, tried to portray "Israel as the Jews' heroic response to Hitler's destruction."[127]

Although his children had non-Jewish mothers, Douglas stated that they were "aware culturally" of his "deep convictions" and he never tried to influence their own religious decisions.[125] Douglas's wife, Anne, converted to Judaism before they renewed their wedding vows in 2004.[5] Douglas celebrated a second Bar-Mitzvah ceremony in 1999, aged 83.[17]: 125

Philanthropy

[edit]Douglas and his wife donated to various non-profit causes during his career and planned on donating most of their $80 million net worth.[128] Among the donations have been those to his former high school and college. In September 2001, he helped fund his high school's musical, Amsterdam Oratorio, composed by Maria Riccio Bryce, who won the school Thespian Society's Kirk Douglas Award in 1968.[129] In 2012 he donated $5 million to St. Lawrence University, his alma mater. The college used the donation for the scholarship fund he began in 1999.[130][131]

He donated to various schools, medical facilities, and other non-profit organizations in southern California. This included the rebuilding of over 400 Los Angeles Unified School District playgrounds that were aged and in need of restoration. The Douglases established the Anne Douglas Center for Homeless Women at the Los Angeles Mission, which has helped hundreds of women turn their lives around. In Culver City, they opened the Kirk Douglas Theatre in 2004.[116] They supported the Anne Douglas Childhood Center at the Sinai Temple of Westwood.[131] In March 2015, Douglas and his wife donated $2.3 million to the Children's Hospital Los Angeles.[132]

Since the early 1990s, Kirk and Anne Douglas donated up to $40 million to Harry's Haven, an Alzheimer's treatment facility in Woodland Hills, to care for patients at the Motion Picture Home.[5] To celebrate his 99th birthday on December 9, 2015, they donated another $15 million to help expand the facility with a new two-story Kirk Douglas Care Pavilion.[133]

Douglas donated a number of playgrounds in Jerusalem and donated the Kirk Douglas Theater at the Aish Center across from the Western Wall.[134]

Politics

[edit]

Douglas and his wife traveled to more than 40 countries, at their own expense, to act as goodwill ambassadors for the U.S. Information Agency, speaking to audiences about why democracy works and what freedom means.[115] In 1980, Douglas flew to Cairo to talk with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. For all his goodwill efforts, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Jimmy Carter in 1981.[116] At the ceremony, Carter said that Douglas had "done this in a sacrificial way, almost invariably without fanfare and without claiming any personal credit or acclaim for himself".[135] In subsequent years, Douglas testified before Congress about elder abuse.[136]

Douglas was a long-time member of the Democratic Party.[137] He wrote letters to politicians who were friends. He noted in his memoir, Let's Face It (2007), that he felt compelled to write to former president Jimmy Carter in 2006 to stress that "Israel is the only successful democracy in the Middle East ... [and] has had to endure many wars against overwhelming odds. If Israel loses one war, they lose Israel."[17]: 226 During the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries he endorsed Michael Bloomberg's campaign.[138]

Role in breaking Hollywood blacklist

[edit]Howard Fast was originally hired to adapt his own 1951 novel Spartacus as a screenplay, but he had difficulty working in the format. He was replaced by Dalton Trumbo, who had been blacklisted as one of the Hollywood 10, and intended to use the pseudonym "Sam Jackson". Trumbo had been jailed for contempt of Congress in 1950, after which he had survived by writing screenplays under assumed names.

Kirk Douglas claimed that it was his insistence that Trumbo be given screen credit for his work that broke the blacklist.[139] In his autobiography, Douglas states that this decision was motivated by a meeting that Edward Lewis, Stanley Kubrick, and he had regarding whose names to list for the screenplay in the film credits, given Trumbo's shaky position with Hollywood executives. One idea was to credit Lewis as co-writer or sole writer, but Lewis vetoed both suggestions. Kubrick then suggested that his own name be used. Douglas and Lewis found Kubrick's eagerness to take credit for Trumbo's work revolting, and the next day, Douglas called the gate at Universal saying, "I'd like to leave a pass for Dalton Trumbo." Douglas writes, "For the first time in 10 years, Trumbo walked on to a studio lot. He said, 'Thanks, Kirk, for giving me back my name.'"[140][verification needed]

In fact, Douglas did not announce Trumbo as the credited screenwriter of Spartacus until August 1960, seven months after producer-director Otto Preminger's January 20, 1960, announcement that he had hired Trumbo to adapt Leon Uris' novel Exodus for the screen. Douglas later successfully denied Trumbo a sought credit on the film Town Without Pity as he worried that his continued association with the screen writer would hurt his career.[141][142] and Kirk Douglas publicly announced that Trumbo was the screenwriter of Spartacus.[143] Further, President John F. Kennedy publicly ignored a demonstration organized by the American Legion and went to see the film.[144][145]

Blogging

[edit]Douglas blogged from time to time. Originally hosted on Myspace,[146] his posts were hosted by the Huffington Post beginning in 2012.[147] As of 2008, he was believed to be the oldest celebrity blogger in the world.[148]

Rape allegation

[edit]Douglas is alleged to have raped actress Natalie Wood in the summer of 1955, when she was 16 and he 38.[149] Wood's alleged rape was first publicised in Suzanne Finstad's 2001 biography of the actress, though Finstad never named the offender.[150]

The allegation received renewed attention in January 2018, after the 75th Golden Globe Awards ceremony paid tribute to Douglas, with several news outlets citing a 2012 anonymous blog post which accused Douglas.[151] In July 2018, Wood's sister Lana said during a 12-part podcast about her sister's life that her sister was sexually assaulted as a teen and that the attack had occurred inside the Chateau Marmont during an audition and went on "for hours".[152] In the 2021 memoir Little Sister: My Investigation Into the Mysterious Death of Natalie Wood, Lana Wood alleged Douglas was her sister's assailant.[149] Douglas's son Michael issued a statement, saying "May they both rest in peace."[149]

Health problems and death

[edit]On January 28, 1996, at age 79, Douglas suffered a severe stroke, which impaired his ability to speak.[153] Doctors told his wife that unless there was rapid improvement, the loss of his ability to speak would probably be permanent. However, after a regimen of daily speech-language therapy that lasted several months, his ability to speak returned, although it was still limited. He was able to accept an honorary Academy Award two months later (in March) and to thank the audience.[154][155] He wrote about this experience in his 2002 book My Stroke of Luck, which he hoped would be an "operating manual" for others on how to handle a stroke victim in their own family.[155][156]

Douglas died at his home in Beverly Hills, California, surrounded by his family on February 5, 2020, at age 103. His cause of death was kept private.[157][158] Douglas's funeral was held at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery on February 7, 2020, two days after his death. He was buried in the same plot as his son Eric.[159][160] On April 29, 2021, his wife Anne died at age 102 and was buried next to him and their son.[161]

Filmography

[edit]In a 2014 article, Douglas cited The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Champion, Ace in the Hole, The Bad and the Beautiful, Act of Love, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, The Indian Fighter, Lust for Life, Paths of Glory, Spartacus, Lonely Are the Brave, and Seven Days in May as the films he was most proud of throughout his acting career.[162]

Radio appearances

[edit]| Year | Program | Episode/source |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | Suspense | "Community Property"[163] |

| 1950 | Screen Directors Playhouse | Champion[164] |

| 1950 | Suspense | The Butcher's Wife[164] |

| 1952 | Lux Radio Theatre | Young Man with a Horn[165] |

| 1954 | Lux Radio Theatre | Detective Story[164] |

Honors and awards

[edit]

- Douglas has been honored by governments and organizations of various countries, including France, Italy, Portugal, Israel, and Germany.[115]

- In 1957, he won the Best Actor award at the San Sebastian International Film Festival for The Vikings.[166]

- In 1958, he was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Fine Arts from St. Lawrence University.[167]

- In 1981, Douglas received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Jimmy Carter.[168]

- In 1984, he was inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.[169]

- In 1990, he received the French Légion d'honneur for distinguished services to France in arts and letters.[115]

- In 1991, he received the AFI Life Achievement Award.[170]

- In 1994, Douglas's accomplishments in the performing arts were celebrated in Washington, D.C., where he was among the recipients of the annual Kennedy Center Honors.[171]

- In 1998, he received the Screen Actors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award.[172]

- In 2002, he received the National Medal of Arts award from President Bush.[115]

- In October 2004, Kirk Douglas Way, a thoroughfare in Palm Springs, California, was unveiled by the city's International Film Society and Film Festival.[173]

- For his contributions to the motion picture industry, Douglas has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6263 Hollywood Blvd. He is one of the few personalities (along with James Stewart, Gregory Peck, and Gene Autry) whose star has been stolen and later replaced.[174]

- 1991 Accepted AFI Life Achievement Award[175]

- 1994 Honoree[176]

- Douglas received three nominations for the Academy Award for Best Actor, for Champion (1949), The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), and Lust for Life (1956), but never won.[167]

- In 1996, he received an Honorary Award for "50 years as a creative and moral force in the motion picture community"[177]

- 1986 Amos nominated for Best Actor in a Mini-Series or Motion Picture Made for TV[178]

- 1968 Cecil B. DeMille Award for Lifetime Achievement[179]

- 1957 Lust for Life won for Best Actor-Drama[178]

- 1952 Detective Story nominated for Best Actor-Drama[178]

- 2002 Touched by an Angel nominated for Outstanding Guest Actor in a Drama Series[180]

- 1992 Tales from the Crypt nominated for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series[180]

- 1986 Amos nominated for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Miniseries or Special[180]

- 1999 Lifetime Achievement Award[181]

- 1963 Lonely Are the Brave nominated for Best Foreign Actor[182]

- 2009 BAFTA/LA award for Worldwide Contribution To Filmed Entertainment[183]

Berlin International Film Festival

- 2001 Honorary Golden Bear[184]

- 1975 Posse nominated for Competing Film[185]

- 1980 Honorary Cesar[178]

- 1997 Lifetime Achievement Award[186]

- 1988 Career Achievement Award[178]

New York Film Critics Circle Award

In 1983, Douglas received the S. Roger Horchow Award for Greatest Public Service by a Private Citizen, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[188]

In 1996, Douglas received an Honorary Academy Award for "50 years as a moral and creative force in the motion picture community." The award was presented by producer/director Steven Spielberg.[154] As a result of Douglas's stroke the previous summer, however, in which he lost most of his speaking ability, his close friends and family were concerned about whether he should try to speak, or what he should say. Both his son Michael, and his long-time friend Jack Valenti, urged him to only say "Thank you", and leave the stage. Douglas agreed, but had second thoughts when standing in front of the audience. He later reflected that: "I intended to just say 'thank you,' but I saw 1,000 people, and felt I had to say something more, and I did."[189] Valenti remembers that after Douglas held up the Oscar, addressed his sons, and told his wife how much he loved her, everyone was astonished at his voice's improvement:

The audience went wild with applause [and] erupted in affection ... rising to their feet to salute this last of the great movie legends, who had survived the threat of death and stared down the demons that had threatened to silence him. I felt an emotional tidal wave roaring through the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in the L.A. Music Center.[2]

Since 2006, the Santa Barbara International Film Festival has awarded the Kirk Douglas Award for Excellence in film to acknowledge lifetime contributions to the film industry. Recipients of the award include Robert De Niro, Ed Harris, Harrison Ford, Michael Douglas, Hugh Jackman, and Judi Dench.[190] The award is typically presented to actors, although directors Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese have been presented with it.[191] In 2015, a star was nicknamed after Douglas in the International Star Registry to commemorate his 99th birthday.[192]

Books

[edit]- The Ragman's Son. Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0671637177.

- Dance with the Devil. Random House, 1990. ISBN 0394582373.

- The Gift. Grand Central Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0446516945.

- Last Tango in Brooklyn. Century, 1994. ISBN 0712648526.

- The Broken Mirror: A Novella. Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 1997. ISBN 0689814933.

- Young Heroes of the Bible. Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 1999. ISBN 0689814917.

- Climbing the Mountain: My Search for Meaning. Simon and Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0743214382.

- My Stroke of Luck. HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 0060014040.

- Let's Face It: 90 Years of Living, Loving, and Learning. John Wiley & Sons, 2007. ISBN 0470084693.

- I Am Spartacus!: Making a Film, Breaking the Blacklist. Open Road Media, 2012. ISBN 1453239375.

- Life Could Be Verse: Reflections on Love, Loss, and What Really Matters. Health Communications, Inc., 2014. ISBN 978-0757318474

- Kirk and Anne: Letters of Love, Laughter and a Lifetime in Hollywood. Running Press, 2017. ISBN 0762462183. With Anne Douglas and Marcia Newberger.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Russian: Иссур Даниэлович; Yiddish: איסור דניאלאָוויטש

- ^ In his autobiography, Douglas explains that for many actors at the time who had unusual or foreign-sounding birth names, a simpler Americanized name was often preferred. His friend Karl Malden, who also changed his name for that reason, made suggestions. Douglas knew that many leading stars at the time had adopted stage names, including Robert Taylor, John Wayne, Cary Grant, and Fred Astaire.[17]: 1–2

References

[edit]- ^ Muir, David (June 29, 2012). "Person of the Week Kirk Douglas on Helping to Break Blacklist". ABC News. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Valenti, Jack. This Time, This Place: My Life in War, the White House, and Hollywood, Crown Publishing (2007) Ch. 12

- ^ Kirk Douglas (1988). The Ragman's Son: An Autobiography. Simon & Schuster. p. 16. ISBN 978-0671637170. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Kirk and Michael Douglas". Land Of Ancestors – Belarus. November 17, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Paskin, Barbra (September 20, 2012). "Hollywood gladiator Kirk Douglas has his eyes set on a third barmitzvah". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ Plessel, John (December 8, 2016). "5 reasons to celebrate actor Kirk Douglas on his 100th birthday". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Darrach, Brad (October 3, 1988). "Kirk Douglas". People. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Kirk Douglas honoured by World Jewish Congress". BBC. November 10, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Freeman, Hadley (February 12, 2017). "Kirk Douglas: 'I never thought I'd live to 100. That's shocked me'". The Guardian. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Spence, Rebecca (July 18, 2007). "A Legend Looks Back: A Visit With Kirk Douglas". The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Farndale, Nigel (July 23, 2011). "Kirk Douglas: in 'pretty good shape' at 94". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ "Other Celebrity Houses of Worship". seeing-stars.com. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Berkvist, Robert (February 5, 2020). "Kirk Douglas, a Star of Hollywood's Golden Age, Dies at 103". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Grondahl, Paul (September 23, 2015). "Funeral for Kirk Douglas' sister in Albany". Times Union. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ "Guideposts Remembers: Kirk Douglas". Guideposts. December 8, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Tugend, Tom. "Kirk Douglas, an iconic star who reconnected to Judaism after near-fatal crash". The Times of Israel.

- ^ a b c d e Douglas, Kirk. Let's Face It, John Wiley & Sons (2007); ISBN 0470084693.

- ^ Douglas, Kirk (2007). Let's face it: 90 years of living, loving, and learning. John Wiley and Sons. p. 3. ISBN 978-0470084694.

- ^ Douglas 1988, p. 19.

- ^ Seemayer, Zach (February 5, 2020). "Inside Kirk Douglas' Relationship With Son Michael Douglas". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ Kindon, Frances (February 6, 2020). "Inside Michael and Kirk Douglas feuds and 'addiction gene' that destroyed family". Daily Mirror. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- ^ Douglas, Kirk (November 5, 2015). "Why I Felt Like a Failure When I Didn't Make It on Broadway". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Tony. The Films of Kirk Douglas. Citadel Press, New York (1991), p. 12; ISBN 0806512172.

- ^ Grondahl, Paul (September 23, 2015). "Funeral for Kirk Douglas' sister in Albany". Times Union. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c Thomas, p. 13

- ^ Thomas, p. 15

- ^ a b Thomas, p. 18

- ^ a b Bacall, Lauren (1978). By Myself and Then Some, London: Coronet, pp. 26–27 ISBN 978-0755313501. OCLC 664201994

- ^ a b "Douglas, Kirk, LTJG". www.navy.togetherweserved.com. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Van Osdol, William R.; John W. Lambert (1995). Famous Americans in World War II: a pictorial history. Phalanx. p. 31. ISBN 978-1883809065.

Serving in the Pacific as an ensign, he was seriously injured because of a premature depth charge explosion and returned to San Diego. After five months hospitalization, he was granted a medical discharge in 1944.

- ^ a b c Parker, John (2011). Michael Douglas: Acting on Instinct, London: Headline. e-book, Ch. 2 OCLC 1194433483

- ^ Smith, Imogen Sara (2011). In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City, Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 103, ISBN 978-0786463053. OCLC 756335120

- ^ Thomas, p. 33

- ^ a b c Thomas, p. 19

- ^ Mosel, Leading Lady: The World and Theatre of Katharine Cornell ISBN 0316585378

- ^ Douglas 1988, p. 146.

- ^ a b Didinger, Ray, and Glen Macnow. The Ultimate Book of Sports Movies: Featuring the 100 Greatest Sports Films, Running Press (2009), p. 260 ISBN 0091521300

- ^ Romano, Frederick V. The Boxing Filmography: American Features, 1920–2003, McFarland (2004), p. 31 ISBN 978-0786417933

- ^ a b c Thomas, p. 28

- ^ "Bryna Productions, Inc". California Secretary of State. September 28, 1949. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, p. 181

- ^ "TCM – Lonely are the Brave". YouTube. April 7, 2013. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- ^ Thomas, p. 64

- ^ Hotchner, A. E. (1975). Doris Day: Her Own Story. William Morrow and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0688029685,

- ^ "Disappearance". mariamusikka.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ "Actor Quizzed on Missing Girl". The San Bernardino Daily Sun. October 13, 1949. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Lyons, Arthur. "The Mysterious Disappearance of Jean Spangler". Palm Springs Life. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ^ Mike Mayo (2008). American Murder: Criminals, Crimes, and the Media. Visible Ink Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-1578592562.

- ^ Lewis, Jon (2017). Hard-Boiled Hollywood: Crime and Punishment in Postwar Los Angeles. Univ of California Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0520284326.

- ^ Sikov, Ed. On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder, New York: Hyperion, (1998) pp. 325–26; ISBN 0786861940

- ^ McGovern, Joe. "A Life in Film: Kirk Douglas on four of his greatest roles", Entertainment Weekly, February 23, 2015.

- ^ Empire Magazine's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time. Archived October 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Empire; retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ Chandler, Charlotte (2002). Nobody's Perfect: Billy Wilder, a Personal Biography, New York: Applause Books, p. 166 ISBN 978-1557836328, OCLC 932564547

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 12, 2007). "'Ace in the Hole' movie review & film summary (1951)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ Phillips, Gene (2010). Some Like it Wilder: the Life and Controversial films of Billy Wilder, Univ. Press of Kentucky, p. 141 ISBN 978-0813125701. OCLC 716971755

- ^ a b Grant, Lee. I Said Yes to Everything: a Memoir, Blue Rider Press (2014) pp. 75, 428–29; ISBN 978-0399169304

- ^ "TCM – Detective Story Intro [Robert Osborne]". YouTube. May 27, 2013. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley. Detective Story review, The New York Times, November 7, 1951; accessed December 26, 2007.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 18, 1955). "Screen: 'Ulysses' Wanders Into Globe; Kirk Douglas Portrays Bewhiskered Hero Silvana Mangano Both Circe and Penelope". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Thomas, p. 7

- ^ "Jam Session at Jacks'", originally telecast on CBS on October 17, 1954.

- ^ Hilmes, Michele. "Kirk Douglas and Bryna Productions". Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015.

- ^ James Bawden; Ron Miller (2016). Conversations with Classic Film Stars: Interviews from Hollywood's Golden Era. University Press of Kentucky. p. 70. ISBN 978-0813167121.

- ^ a b "Dot Acquires 'Viking' Track" (PDF). Billboard. April 21, 1958. p. 5.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office. (1958). Catalog of Copyright Entries 1958 Music July–Dec 3D Ser Vol 12 Pt 5. United States Copyright Office. U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- ^ Hughes, David (2013). The Complete Kubrick. Random House. p. 36. ISBN 978-1448133215.

- ^ Monush, Barry (2003). The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors, Applause Books, p. 200 ISBN 978-1557835512, OCLC 472842790

- ^ a b LoBrutto, Vincent (1997). Stanley Kubrick: A Biography, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, pp. 105, 135 ISBN 978-0786704859, OCLC 1037232538

- ^ a b Thomas, p. 24

- ^ "Rich Little roasts Kirk Douglasipad". YouTube. December 19, 2013. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ "David Frye Doing Kirk Douglas, LBJ, Rod Steiger & Brando Impersonations". YouTube. January 13, 2015. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Fairbanks, Brian. Brian W. Fairbanks – Writings, Lulu (2005) e-book

- ^ McElhaney, Joe (2009). Vincente Minnelli: The Art of Entertainment, Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press. p. 300 ISBN 978-0814333075. OCLC 232002215

- ^ Niemi, Robert (2006). History in the Media: Film and Television, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 296 ISBN 978-1576079522. OCLC 255629433

- ^ Douglas 1988, p. 266.

- ^ a b Thomas, p. 44

- ^ Naremore, James (1993). The Films of Vincente Minnelli, Cambridge Univ. Press, p. 41, ISBN 978-0521387705, OCLC 231580819

- ^ Pfeiffer, Lee (n.d.). "The Bad and the Beautiful". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ a b c d e Douglas, Kirk; Douglas, Anne; Newberger, Marcia (2017). Kirk and Anne: Letters of Love, Laughter and a Lifetime in Hollywood (Hardcover). Philadelphia: Running Press. pp. 67, 101, 103, 104, 113, 114, 115, 121, 122. ISBN 978-0-7624-6217-9.

- ^ Samuelson, Kate (December 9, 2016). "3 Things to Know About Kirk Douglas on His 100th Birthday". Time. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ Thomas, p. 168

- ^ Thomas, p. 149

- ^ Meroney, John; Coons, Sean (July 5, 2012). "How Kirk Douglas Overstated His Role in Breaking the Hollywood Blacklist". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ "'Trumbo's' Dean O'Gorman plays Kirk Douglas and earns praise from the legend", Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2015.

- ^ Douglas, Edward (2009). Jack: A Biography of Jack Nicholson, HarperCollins, p. 136 ISBN 978-0061745492. OCLC 1237159010

- ^ Armstrong, Stephen B. ed. (2013), John Frankenheimer: Interviews, Essays, and Profiles, Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, p. 166, ISBN 978-0810890572. OCLC 820530958

- ^ "New Double Bill". The New York Times. August 3, 1967. p. 0. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Hunter, Allan. Faye Dunaway, St. Martin's Press, NY (1986) p. 81

- ^ Dunaway, Faye; Sharkey, Betsy (1995). Looking for Gatsby: My Life , Simon & Schuster, p. 193 ISBN 978-0684808413, OCLC 474923659

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Farber, Stephen (November 2, 1986). "Lancaster and Douglas: A Chemistry Lesson". New York Times.

- ^ "Liberty Receives Classical Salute". July 5, 1986. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (December 10, 1999). "'Diamonds' Gives Douglas a Chance to Sparkle". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b "Silver screen veteran Kirk Douglas celebrates 100th birthday". The Irish Independent. Press Association. December 9, 2016.

- ^ Timothy Shary; Nancy McVittie (2016). Fade to Gray: Aging in American Cinema. University of Texas Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-1477310632.

- ^ "Illusion (2004)". BFI. Archived from the original on November 3, 2017.

- ^ Olivier, Ellen (January 17, 2010). "Kirk Douglas' 'Before I Forget' movie premieres; South Coast Repertory's 'Ordinary Days' has West Coast opening". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ "Inside Kirk Douglas's intimate 100th birthday celebration". The Telegraph. Associated Press. December 10, 2016. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ Johns, Gibson (January 8, 2018). "Kirk Douglas, 101, Makes a Rare Public Appearance at the 2018 Golden Globes". Aol.

- ^ Birkinbine, Julia (January 7, 2018). "Kirk Douglas, 101, made a very rare public appearance at the 2018 Golden Globes". Closer Weekly.

- ^ Thomas, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, p. 21

- ^ Thomas, p. 25

- ^ Thomas, p. 22

- ^ Darrach, Brad (October 3, 1988). "Kirk Douglas". People. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Turan, Kenneth (August 14, 1988). "The Wrath of Issur: The Ragman's Son by Kirk Douglas". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Douglas, Kirk (1989). The Ragman's Son: An Autobiography. G.K. Hall. pp. 194–200, 206, 208–12, 224–228, 231–233, 238–43, 248, 335. ISBN 0-8161-4795-7.

- ^ Tugend, Tom (May 25, 2017). "New book reveals a lifetime of love letters between Kirk Douglas and wife". Jewish Journal. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Kirk & Anne Douglas". The Heart Foundation. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ a b c Douglas, Kirk. "Kirk Douglas looks back at 60 years of marriage", Los Angeles Times, June 20, 2014.

- ^ "Douglas son 'died accidentally'". BBC News. August 10, 2004. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Vargas, Chanel (August 9, 2017). "Kirk Douglas' Six-Decade Love Story With His Wife, Anne Buydens". Town & Country Magazine. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ Carter, Maria (May 3, 2017). "Kirk and Anne Douglas Open Up About Their Tumultuous Marriage in New Tell-All Book". Country Living. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Douglas, Douglas with Newberger. Kirk and Anne: Letters of Love, Laughter and a Lifetime in Hollywood, pp. 104–106

- ^ Gorman, Gary; O'Donnell, Santiago (February 14, 1991). "2 Die as Plane, Copter Crash; Kirk Douglas, 2 Others Hurt". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ "Kirk Douglas, Noel Blanc Recovering After Air Collision That Killed Two". AP NEWS. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Lacher, Irene (September 24, 1997). "A Role Made to Order". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Tugend, Tom (February 6, 2020). "Kirk Douglas, Legendary Movie Star Who Had His Second Bar Mitzvah at 83, Has Died". The Jewish Week.

- ^ a b c Douglas 1988, p. 383.

- ^ Douglas, Kirk (March 4, 2000). "Climbing the Mountain: Essay and Interview with Kirk Douglas". aish.com. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- ^ Moore, Deborah. To the Golden Cities: Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A., Harvard Univ. Press (1994) p. 245

- ^ Feinberg, Scott (August 20, 2015). "Why Kirk and Anne Douglas Are Giving Away Their Fortune". Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Cudmore, Bob. "Oratorio describes life in the city", The Daily Gazette, September 30, 2001

- ^ "Kirk Douglas donating $5 million to St. Lawrence University", Associated Press, July 30, 2012.

- ^ a b Kilday, Gregg (July 27, 2012). "Kirk and Anne Douglas Donate $50 Million to Five Non-Profits". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Coleman, Laura. "Kirk, Anne Douglas Donate $2.3M To Children's Hospital Los Angeles" Archived March 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The Beverly Hills Courier, March 26, 2015.

- ^ Shah, Yagana (December 16, 2015). "Kirk Douglas Just Did Something Beautiful For His 99th Birthday". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Boruch (December 14, 2017). "Kirk Douglas and His Theatre in Jerusalem". Times of Israel.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter: Presidential Medal of Freedom Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony". Presidency.ucsb.edu. January 16, 1981. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Paskin, Barbra. "Hollywood gladiator Kirk Douglas has his eyes set on a third barmitzvah" Archived October 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Jewish Chronicle, September 20, 2012.

- ^ Shaw, Tony (2022). Hollywood and Israel: a history. Columbia University Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780231544924.

- ^ D'Zurilla, Christine (February 11, 2020). "Kirk Douglas' last words? Michael Douglas says they were a political endorsement". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ Trumbo (2007) at IMDb Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ Kirk Douglas. The Ragman's Son (Autobiography). Pocket Books, 1990. Chapter 26: The Wars of Spartacus.

- ^ Meroney & Coons, John & Sean (July 5, 2012). "How Kirk Douglas Overstated His Role in Breaking the Hollywood Blacklist". atlantic.com. The Atlantic. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Nordheimer, Jon (September 11, 1976). "Dalton Trumbo, Film Writer, Dies; Oscar Winner Had Been Blacklisted". The New York Times. p. 17. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

...it was Otto Preminger, the director, who broke the blacklist months later by publicly announcing that he had hired Mr. Trumbo to do the screenplay

- ^ Harvey, Steve (September 11, 1976). "Dalton Trumbo Dies at 70, One of the 'Hollywood 10'". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

He recalled how his name returned to the screen in 1960 with the help of Spartacus star Kirk Douglas: 'I had been working on Spartacus for about a year'

- ^ Schwartz, Richard A. "How the Film and Television Blacklists Worked". Florida International University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ "1960: January 20; Hollywood Blacklist Broken – Producer Otto Preminger Credits Dalton Trumbo for "Exodus" Script". todayinclh.com. Today in Civil Liberties History. May 21, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Kendall, Nigel. "World's oldest blogger María Amelia López Soliño dies", Times Online, May 22, 2009; accessed May 25, 2009.

- ^ Kirk Douglas blog Archived June 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Huffingtonpost.com; retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ Irvine, Chris (December 17, 2008). "Kirk Douglas becomes MySpace's oldest celebrity blogger". Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2020 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ a b c Italie, Hillel (November 4, 2021). "Natalie Wood was assaulted by Kirk Douglas, sister alleges". Associated Press. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Thomson, David (January 14, 2020). Sleeping with Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-10197-102-4.

- ^ Wulfsohn, Joseph A. (January 7, 2018). "Twitter Calls Out Globes For Honoring Kirk Douglas, Accused of Raping Natalie Wood". Mediaite. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Chan, Anna (July 26, 2018). "Lana Wood: Natalie Wood was sexually assaulted as a teen". AOL. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Douglas, Kirk; Gold, Todd (October 6, 1997). "Lust for Life". People.

- ^ a b "Kirk Douglas receiving an Honorary Oscar®". YouTube. April 24, 2008. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Cooper, Chet (2001). "Interview: Kirk Douglas". Ability. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Alikhan, Anvar (October 24, 2016). "Thespian, gambler and time traveller: the remarkable 100-year run of Kirk Douglas". scroll.in.

- ^ McLellan, Dennis (February 5, 2020). "Kirk Douglas dead at 103; 'Spartacus' star helped end Hollywood blacklist". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Berkvist, Robert (February 5, 2020). "Kirk Douglas, a Star of Hollywood's Golden Age, Dies at 103". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ Fernández, Alexia (February 7, 2020). "Michael Douglas, Catherine Zeta-Jones and More Attend Kirk Douglas' Funeral 2 Days After His Death". People.

- ^ "Kirk Douglas Laid to Rest at Private Funeral 2 Days After Death". E! Online. February 7, 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Mike (April 29, 2021). "Anne Douglas, Philanthropist and Widow of Kirk Douglas, Dies at 102". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Douglas, Kirk (December 9, 2014). "I've Made About 90 Feature Films, but These Are the Ones I'm Proudest Of". The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ "Suspense – Community Property". Escape and Suspense!. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Those Were the Days". Nostalgia Digest. Vol. 42, no. 4. Autumn 2016. p. 35.

- ^ Kirby, Walter (March 2, 1952). "Better Radio Programs for the Week". The Decatur Daily Review. The Decatur Daily Review. p. 42. Retrieved May 28, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "San Sebastian Film Festival". sansebastianfestival. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Barnes, Mike (February 5, 2020). "Kirk Douglas, Indomitable Icon of Hollywood's Golden Age, Dies at 103". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ "Jimmy Carter: Presidential Medal of Freedom Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony". Presidency.ucsb.edu. January 16, 1981. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Great Western Performers – National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum". April 19, 2019. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.